The Cost of Cash...lessness

Source: asomo.co

Author: Brett Scott

Note: I'm in South Africa right now without my recording equipment, so the audio version will be released in a couple weeks

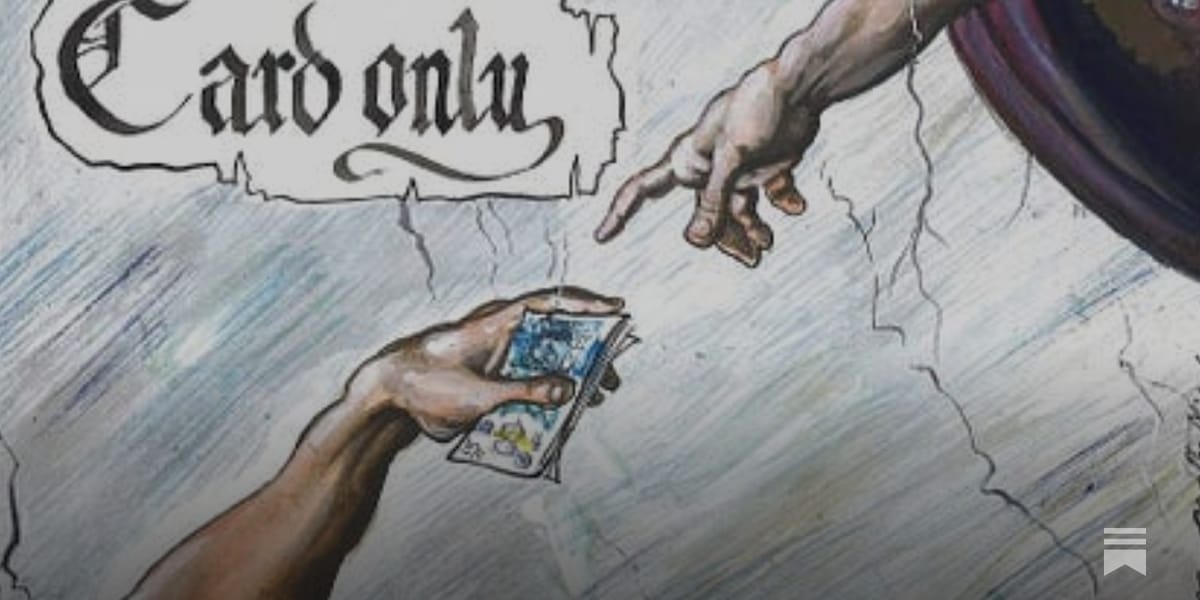

When I'm defending physical cash I sometimes catch public attention by focusing on scandalous problems that can accompany 'cashless' bank payment systems. These include surveillance, authoritarian censorship, cyberwarfare, hacking, exclusion, and domination by corporations (see 10 Reasons to Fight Cashless Contagion). The fintech industry, by contrast, studiously avoids talking about these 'political' things, and focuses rather on 'economic' considerations like innovation and efficiency. In the fintech worldview, cash is neither innovative nor efficient, which means it must give way to digital payments like a horsecart moving aside for sportcars.

Their progress narrative can be destabilized by simply recasting cash as the bicycle of payments (and digital as the Uber, rather than the sportcar), but their rhetoric remains powerful and disorientating for the public. The language of innovation is the native tongue of entrepreneurs, and for a long time that's been politically untouchable - who would ever dare to be against innovation? The language of efficiency is borrowed from conventional economists, but it's equally politically untouchable. In the neoliberal era, governments have been desperate to show that they opt for the cheapest path, and if it's narrowly more efficient for society to slump into dependence on an oligopoly of centralized firms (and to be under the thumb of tech and finance billionaires) then so be it.

This imagined split between 'economic' and 'political' considerations is problematic on many levels, but it's hammered into the minds of undergraduates in many university economics programmes. Wannabe economists don't begin their analysis by imagining people formed within tangled webs of culture and politics. Rather, they open their introductory textbooks and are faced with an image of 'units' - discrete and self-contained agents - who seek to get the most from the least.

Even nuanced economists will have been exposed to this idea of the economy as a collection of independent units who seek out the most efficient and 'rational' way to maximize their utility. It's not that these economists are unable to recognise political, cultural, and even 'irrational', weird and creative aspects of society. It's that economic analysis requires them to strip those away from multi-dimensional issues in order to isolate an imagined economic essence. This is revealed in statements like 'I can't explain the politics of this, but I can explain the economics'.

This illusory split gets particularly problematic in the monetary realm. Econ graduates are trained to see money as a purely 'economic' phenomenon, rather than a political one. To this end, they're fed an abstract account of money as an apolitical commodity subject to natural market evolution, as if it were a product on a market, rather than a deeply political structure that underpins markets. Rather than meditating on how this market-underpinning foundation is laid down and maintained, they treat it as if it were just another commodity and try to apply market logic to understand it (which, incidentally, is why economists love creating 'evolution of money' stories in which they fantasize a trajectory from barter to shells to metals to cash to credit cards).

This mental glitch, in which money is seen as a product rather than a foundation, wreaks havoc when trying to understand the case of cashless society. I remember the blank look on the face of an award-winning economist when I explained to him that the move towards 'cashlessness' is heavily pushed by the banking sector, which fights dirty for the ascendency of its digital casino chips (the so-called 'deposits' that we see our bank accounts - see The Deposit Myth). I suggested to him that, ironically, the attack on cash weakens the structural integrity of the monetary foundation that these banks themselves depend on. He didn't get it. Not only was he unaware of the fact that banks issue their own casino-chip money, but he couldn't grasp why this might be important. The only relevant fact to him was that the digital payments they facilitated were 'efficient and convenient', and were thereby a superior product. In the economics worldview, trying to go against that is like trying to stop water running down a hill.

Let's take a detour into that metaphor above. Water is pulled down a hill by gravity, and it's not like water chooses or desires this. When we move towards things, however, economists tend to assume that it must stem from an internal and independent desire within us, which pushes us towards the thing. This becomes a foundational vibe in their analysis. For example, when our desires hit against constraints, they're supposed to be resolved by 'market forces' that will generate signals that guide society down some optimal path to get the most from the least. This feeds into dominant progress narratives, in which desire-driven economic agents accumulate more and more stuff and carry society to a new 'high score' (see Money as Addiction).

But if Economics is synonymous with 'market forces', many conventional economists seem reluctant to fully embrace the implications of that word 'force'. We're certainly tied up in large-scale markets, but what if those markets subjected us to forceful forms of 'gravity' that could override - or condition - our internal desires, and pull us towards paths of least resistance? Rather than being independent units, we're all caught in interdependent webs, and nowadays those webs have been massively scaled-up to the point where their default settings easily overcome, and mould, our individual desires.

The primary default setting is to expand and accelerate, and going against this path can feel like being a water molecule trying to move uphill. This is why people who find cash totally normal have a growing feeling that the option to use it will be taken away from them. They can sense the systemic tendency pulling everyone towards ever more automation and acceleration, and struggle to imagine how they'd move against it. It's this uphill path that requires active choice, whereas going with the systemic tendency is a passive act of releasing resistance, allowing yourself to be pulled towards the systemic default.

In a city like London there are millions of people who remember living with debit cards and apps without feeling any strong necessity to use them all the time. Like social smokers, however, they would experiment with them. After a while they started to feel the pull getting stronger, and noticed the alternative options slowly disappearing, after which it felt inexorable. They're left with a feeling like that society must have 'chose' that, but nobody can remember an exact moment when this shift happened, and they're currently in the process of slowly forgetting what it was like before it happened. Many people are vaguely aware of how their neural pathways have been rearranged into new circuits of addiction, and now find themselves agitated by situations they previously were not agitated by - like the thought of taking out a banknote in a bouji London bar rather than simply tapping their card. At some level they understand that they're stuck in a vast web that will literally break them if they refuse to 'choose' the path of increased acceleration. If they try to go 'uphill' through acts of actual choice, they'll be increasingly blocked. This imminent blocking is why we find so many stories expressing concern about those who'll be 'left behind' by cashless society...

So, asking when Londoners' chose to transition to bank-dominated digital payments is misleading, because they were slowly sucked into them. All of this is missed by (unnuanced) economists, because the 'units' in their textbooks start life in some gravity-free world, sheltered from systemic forces, cultural conditioning, peer pressure, or hegemony (where the interests of a ruling elite seep into our souls as 'common sense'). So, when they see a man tapping his ApplePay, they see an act of desire and choice. They don't see a man sliding into a new state of accelerated addiction after his brain has been hacked by endless nudging amidst decades of bank lobbying and shut-downs of the cash infrastructure. They won't recognise that he'll increasingly be punished and feel 'out of sync' if he doesn't move in this direction. They'll imagine he's stepping forward into the future, rather than slumping into conformity.

Share

This slumping is now easily visible on plane flights. A few years ago it was common for people to take out cash in an act of choice, but EasyJet executives - and all the other airline execs - decided in boardrooms to take that choice away. Those were political acts imposed from above, and those acts of blocking create shame that transmits like a cultural virus. People have now rearranged their behaviour to avoid it. They literally learn to have their cards at the ready, after which they come to expect it, and - once addicted - want it. This is easy to observe if you have anthropologist eyes, rather than economist goggles. Just visit a place where cash is considered normal. The people don't perceive any inconvenience, because they've not yet learned to feel shame about cash.

This is not unique to cash. This same phenomenon occurs with all automation processes in our economy. A few years ago we barely noticed the absence of AI, but right now all of us are in the process of learning to want, or at least expect it. We're at the beginning phase of new slumping process, and at some point you'll be forced to sink into dependence on it. Conventional economists frequently just ignore the econo-political-cultural forces that can create this 'gravity', and this approach gets spun by the fintech industry. They dripfeed us a powerful ideology that says automation is pushed by our desire, but is also unstoppable, and thereby completely indifferent in our desire (don't get left behind!).

Fintech firms like the German digital bank N26 will present themselves as innovators serving this transition, but also as efficiency-mongers reducing cost to society. This takes us back to their story of cash being an inefficient and old-school 'horsecart' exerting a costly drag on the economy.

In the piece above, N26 propagandists lay down a range of costs that the cash horsecart supposedly exerts on our society. They're not alone in doing this. It's common for fintech players to raise concern about the 'cost of cash'. These costs include the cost of printing it (incurred by money issuers), the cost of banking it, insuring it, moving it around, and the time taken to do reconciliation (incurred by businesses). They harp on about the hassle of using it, the time taken to go to ATMs, and the interest not earned by not using bank accounts. They set that against their digital systems, and invoke the illusory mantra that technology saves you time, rather than simply accelerating your life (see Tech doesn't make our lives easier. It makes them faster).

One of the reasons why the propaganda works is that it plays into existing weaknesses in economic literacy. An economy is a interdependent web of people who draw from the earth, but nowadays that takes the form of a giant transnational mesh structure underpinned by state legal systems and multi-tiered monetary systems. Modern corporate capitalism is actually a vast network vortex, with sub-vortices.

Rather than experiencing all the underlying connections within this vortex-of-vortexes, a person will experience themselves like a disconnected atom moving from one market to the next. At one point they're a consumer in the goods market, the next an employee in the job market, and the next an investor in the financial market. In each of these spaces they're but one tiny node, and rather than recognizing the interlocking nature of the markets they pass through, they experience themselves like a blindfolded person moving around an elephant, imagining each part they touch to be a unique object.

When someone is immersed in a huge system that's too large to see, it's easy to get them to fixate on the 'phenomenological' elements directly in front of them, rather than the reality beyond their perception. The interlocking markets of corporate capitalism are held together by monetary systems, but many people casually adopt the economics view of money as some kind of mysterious special commodity. We often fixate upon on monetary cost, the amount of monetary credits handed over to get something in an act of exchange, while not noticing that the most primal cost of something is a real resource cost - the amount of human energy and natural resources that go into bringing it to life through an act of production. A monetary cost is one leg of an exchange, and the other is a real good or service which exacted a real resource cost on its producers, and which is the actual thing that (theoretically at least) gives us some benefit. The good or service gets used up, but money doesn't. Once handed over, the money will continue on an onward path that may fork and make its way back to you somewhere else in the multi-dimensional vortex (or will be pulled out of circulation by its issuers).

Fintech propagandists, though, can mobilize misunderstandings about this structure to their advantage in at least three ways:

Let's take an example from the N26 article, where they claim that:

Cash needs to be printed, continually inspected and then transported to and secured in safes. That costs the German economy over €10 billion each year.

They're trying to imply that the €10 billion is like a gas lost to space, but those monetary costs will appear on a bunch of income statements somewhere else as income earned from providing a service, and will turn up in GDP figures. Indeed, everything that turns up in GDP 'costs' one party money, and another party real resources, but we tend to assume there's also a reverse flow of benefit to these costs. Indeed, things often incur a higher monetary cost if they're valuable. High quality jeans cost more than cheap shirts because they're better. Similarly, a monetary system with cash is a more resilient, balanced and inclusive monetary system, which is better. Of course there's a real resource cost to producing jeans, and to maintaining the cash system, but there's also a real resource cost to maintaining an army, a logistics system, or stairs in a skyscraper. Sometimes we use resources for valid reasons.

The best way to understand our N26 propagandist is to see them like an elevator salesperson spinning stories about the wonderous innovation and efficiency of their automated solution, while casting stairs as a wasteful and costly use of resources. I could imagine an ancient Pharoah ordering the creation of a collossal pyramid of gold-encrusted stairs in a wanton act of wastefulness, but - on average - our use of real resources for stairs is totally valid. While the elevator evangelist harps on about the exertion required to walk up them, fitness instructors would see that as a benefit. Moreover, the costs of stairs can prevent far more serious 'social costs', like people getting trapped in a building when it's burning down.

An elevator salesperson would undoubtedly draw attention to people tripping down stairs and breaking their leg, much like our fintech propagandists who do everything they can to draw attention to social costs of cash. In the N26 piece they highlight 'all the illegal activity in Germany associated with cash', and the 'astronomical sums of cash' that are lost or stolen. They ignore the fact that digital systems are constantly used for cybercrime, hacking, extortion and tax avoidance (ahem, the entire offshore tax system is facilitated via digital bank accounts), but the 'cash as crime' line is a major tool in the anti-cash lobby's arsenal.

The figurehead for this is none other than Björn from ABBA, who has been spearheading a campaign against cash ever since his son's apartment got burgled in 2008. Nobody was harmed in this incident, but Björn was evidently outraged, because it led to him becoming Sweden's foremost proponent of getting rid of cash entirely. He laid out this challenge in 'cost vs. benefit' terms:

It's a classic case of non-holistic and non-systemic thinking, because in focussing on the trauma that could emerge when cash is around, Björn fails to reflect on all the trauma that could emerge when it isn't. He isn't particularly interested in the trauma stemming from payments surveillance, or the trauma experienced by those shut out by authoritarian states who can turn off their ability to survive by blocking their digital payments. He's not particularly fussed by the humiliation and discrimination people face for lacking the means - or desire - to use digital infrastructures. He's not interested in the deaths that could result from digital systems meltdown, or the life savings lost to hacked digital accounts, or the elderly person in South Africa being flustered by a smooth-talking con-man into giving out digital bank details via a phone call or email scam (or at gunpoint in their home). He's not interested in the fact that platforms harvest our data - including payments data - to segment, isolate and manipulate us, a factor that is leading to increased political disorientation and polarization. Hell, for all he knows, that disorientation increases our chances of war.

But he is very angry about his son being burgled, so much so that he wants your kids to be securely tethered into Big Finance-Tech for the rest of their lives, and to have to hand over fees to MasterCard and the banking sector to do even the simplest things like selling lemonade on the street. He doesn't care about the fact that their future will be one in which digital corporates dominate over the political system. He's indifferent to the fact that the same banks that control the digital payments system also did things like cause the 2008 Financial Crisis, which destroyed the livelihoods of millions of people, and indirectly led to the deaths of who knows how many.

In fact, Björn actively embraces this state of corporate domination as modern. Here he is, quoted in a Wired piece from 2016:

Björn, of course, is so in touch, because he's a guy with $300 million who cites Bill Gates as the person he admires most, and who believes it's self-apparent that progress means yoking ourselves into a Big Tech complex designed to extract data and fees. Let's be blunt. ABBA produced some good tunes, but they were never exactly... political.

There are real costs to cash, but those comes with real benefits, the absence of which can bring real social costs, which are really just real losses to our wellbeing. Monetary costs, real resource costs, and social costs are not the same, albeit there are complex interconnections between them.

The shallow rhetoric of the fintech industry does no justice to these subtle concepts, and shows ignorance of the actual monetary system. The actual monetary system is a politically anchored multi-layered web of IOUs, in different forms, that holds the so-called economic realm together. Analysing the separate elements of that foundation as if they were free-floating commodities subject to monetary cost considerations (that the foundation itself underpins) is delusional on multiple fronts. Not only does the foundation get weakened if you remove cash, but we incur all those social losses: exclusion, centralization of power in too-big-to-fail oligopolies, inequality that stems from centralization, data extraction used to disorientate us, and acceleration that raises our bloodpressure. We can have a debate about the relative severity of these 'political' losses, but never let the fintech industry tell you these are side issues. Money is political, and that's the starting point of the economics of cash.